Devil’s Den and Basin, Newbury, Massachusetts

Last Updated: 21st Jan 2024By Peter Cristofono

Devil’s Den and Basin, Newbury, Massachusetts

© 2012 Peter Cristofono, Salem, Mass.

Adapted from BMC News, vol 76, issue 5, May 2012

Updated, December, 2015.

Introduction

For more than two hundred years, the minerals from the metamorphosed impure magnesian limestone deposits at Devil’s Den and Devil’s Basin in Newbury have fascinated mineralogists and mineral collectors. Located just a few miles from the coastal town of Newburyport, the overgrown and abandoned quarries are so old that by the 19th century some had forgotten their origins, and they were sometimes mistaken for natural rock formations. Today these quarries are seldom visited by collectors. The Den is located in a densely wooded area with no clear trail to it, though it is apparent from graffiti on the quarry walls that local teenagers still frequent it, as they did centuries ago. The Devil’s Basin is in a forested wildlife management area and is little visited and hard to find; the many moss-covered rocks on the ledges and ancient dumps show it hasn’t been explored much in recent years.

History

On crisp autumn days in the early 1800s, in the fields and orchards surrounding Newburyport, groups of adventurous boys would collect apples by knocking them down from trees with poles and filling their bags until they were chased away by angry farmers. They would sometimes escape to a favorite rocky hideout, a mysterious pit and cavern they called Devil’s Den. This secluded place, far from the village, appeared to be guarded by three ghostly poplar trees. To avoid antagonizing the forces of darkness they believed controlled this rocky outpost, a new boy would have to undergo an initiation rite before entering the Den. The rite would take place at a large solitary boulder called Devil’s Pulpit, located in a pasture several hundred feet south of the Den. In a solemn ceremony, the boy would climb to the top of the boulder and repeat certain words, said to be “not very reverent,” so as to be protected from the evil power which the Lord of the Den might unfurl. It was claimed that the Devil himself would preach from this rock at midnight, to his infernal crew gathered at its base. Even after properly initiated, a person wouldn't dare enter the Devil’s Den alone. This was because there was said to be "a name" carved in the ground near the entrance to the Den, past which no creature traveling alone would return alive. The boys’ imaginations were primed by having read German tales of sorcery, and so they shuddered as they recalled the “authentic traditions” of the Devil’s Den. (Felton, 1854; Lunt, 1873)

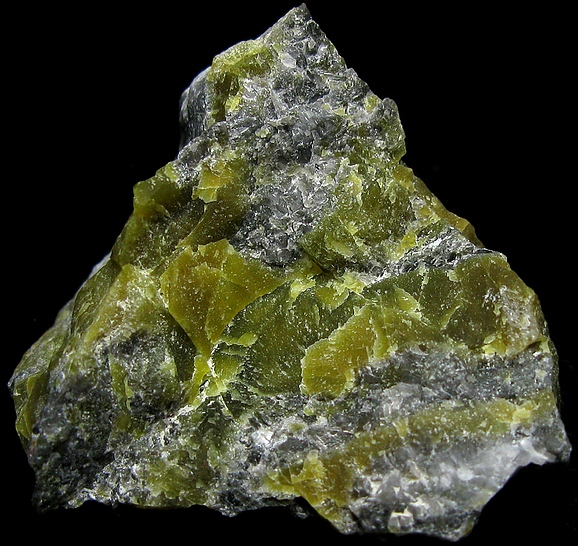

Inside the confines of the Devil’s Den, a treasure trove of intriguing stones could be found, notably gemmy green precious serpentine. Frequently interspersed with massive serpentine was silky, fibrous chrysotile. The Newburyport boys called this asbestos mineral “rag-stone” and they would chew it like gum. In an 1859 poem, John Greenleaf Whittier described it as “gray earth-flax.”

The origin of these quarries dates to 1697 when Ensign James Noyes (1657–1723) of Newburyport discovered “lime-stone” in Newbury (Sewall, 1697). This was a valuable discovery both for the economy of the town and for the colony. At the time, the only source of lime to make mortar for construction purposes was from oyster and clam shells. However, by the 1730s, quarries of better quality limestone, especially in Thomaston, on the coast of Maine, rendered the Newbury quarries obsolete, and they were eventually abandoned.

How these quarries were named is a mystery, but we can be sure that they were not named by the good townspeople of Newburyport in 1697. This was only five years after the infamous outbreak of witchcraft hysteria in nearby Salem. In fact, Ensign James Noyes' older brother, Rev. Nicholas Noyes II (1647–1717), was a minister in Salem who officiated at hangings of accused witches. And one of James' cousins, Sarah Noyes Hale (1656–1697) of Beverly, was herself accused of witchcraft in 1692 by a 17-year old girl who accused both Sarah and the ghost of Mary Eastey (an executed "witch") of afflicting her. Sarah was never officially charged however, perhaps because her uncle was the powerful Reverend Noyes. In 1679–1680, more than a dozen years before the Salem witch trials, the town of Newbury went through its own occult scare when the home of the Morse family was said to have been repeatedly attacked by invisible stone-throwing demons, according to the Rev. Cotton Mather (1663–1728). Goody Morse was charged with witchcraft and sentenced to death, but her sentence was later overturned on appeal. The earliest published use of the name "Devil’s Den" seems to have been by “B.P.” (1819), but the name was coined before that. For instance, Rev. William Bentley of Salem wrote in his diary about a visit to "the Devil's Den" with "Mr. S & the ladies" on September 28, 1813 (Bentley, 1813). Currier (1896) says the “young and credulous” in the early part of the nineteenth century had found traces of the Devil’s footprints in the rocks at the site, but long before these were found, “pleasure parties” had visited during the summers and entertained one another with eerie stories featuring the Prince of Darkness.

Parker Cleaveland

If some of the local kids were visiting Devil’s Den on a certain morning in the first week of June, 1811, they would have encountered the young scientist known today as the father of American mineralogy, Prof. Parker Cleaveland (1780–1858) of Bowdoin College. The professor had grown up in the Rowley–Newbury area and was visiting family at the time of his excursion. His half-brother, Rev. Dr. John P. Cleaveland (1799–1873), later recalled the day: “I well remember the forenoon of a warm day… when he made his first visit to the Devil’s Den in Newbury... It had been visited once before by a Professor from Harvard, and once by some Professor from foreign parts; but its riches were reserved for my brother’s eye. He returned to my father’s house with one or two candle-boxes filled; and my mother’s kitchen was at once turned into a laboratory, and the floor strewed with fragments of every variety which the den yielded... No miser ever worshipped his money as he did these specimens. Many of them which I helped him reduce and pack up that day have long had a place in French, German, and Russian Cabinets.” (Woods, 1859; Ewell, 1904)

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) had in his possession a purse made of wood and a fibrous asbestos mineral (or "salamander cotton" as it was locally known) that might have come from Newbury. In 1724, at the age of 18, Franklin brought the purse with him to London and sold it Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), collector, scientist and founding father of the British Museum. It is still in the British Museum today. Harvard mineralogist Clifford Frondel (1907–2002) thought the mineral used to make the purse was most likely from Newbury. He called the material “a silky type of tremolite asbestos” identical to that of Newbury asbestos (Frondel, 1988). However, most reports have identified Devil’s Den asbestos as fibrous serpentine or chrysotile (Crosby 1880, 1888; McDaniel, 1884; Dana, 1892; Sears. 1905; Krumm & Teichman, 1958). If the purse is made of tremolite, the material almost certainly did not originate in Newbury; but if chrysotile, it might well have come from Devil's Den.

Other asbestos deposits in Newbury have been mentioned in early reports. The editor of a Richmond, Virginia newspaper, identified only as “V.P.” by the National Register (1816) said that he remembers seeing several large pieces of asbestos in 1794 on Kent Island in the Parker River, with some filaments being nearly three inches in length. He was told at the time that there were large quantities of asbestos on the island. B.P. (1819) also says that asbestos occurs on Kent’s Island and on the banks of the Parker River as well.

Jacob Perkins

The well-known inventor Jacob Perkins of Newburyport, once produced a number of incombustible bank notes using paper made out of Newbury asbestos. This currency that wouldn't burn was a “novelty” at that time that surprised his friends (H. C. Perkins, 1864).

Later History of Devil’s Basin

In 1877, the Devil’s Basin quarry was owned by Richard S. Spofford, Jr. (1833–1888), lawyer and husband of Harriet Prescott Spofford (1835–1921) of Newburyport, noted poet and author of gothic romances. The fireplace in their Deer Island home was made from green precious-serpentine-rich rock from the quarry, indicating that it was worked at least in this instance for architectural stone.

Minerals of Devil’s Den and Basin

The following is a list of species reported from these two localities, along with the authors and dates of the published reports. This list is largely historical; in many cases modern analyses are lacking.

Carbonates

Calcite CaCO3 was reported by McDaniel (1884), Essex Inst. (1885), Crosby (1888), Sears (1894, 1905), Boston Mineral Club (1949) and Krumm & Teichman (1958). The variety satin spar was reported by Warren and Jackson (1813), Hitchcock (1833, 1841) and Clapp & Ball (1909). Robinson (1825) referenced John W. Webster in noting that the “asbestos” of the locality had been mistaken for satin spar.

Dolomite CaMg(CO3)2 was reported by Coffin & Bartlett (1845), Perkins (1864), McDaniel (1884), Essex Inst. (1885), Crosby (1888), Sears (1905) and Krumm & Teichman (1958).

Siderite FeCO3 was reported by Nason (1876) as carbonate of iron; and by Crosby (1880), McDaniel (1884) and Dana (1892). Essex Inst. (1885) reported chalybite, a synonym for siderite.

Sulfides

Arsenopyrite FeAsS was listed by Dwight (1833) as arsenical iron pyrites occurring in Newbury along with marble, serpentine, etc. but it is unclear whether this is from Devil’s Den or Basin or from elsewhere in the town. Rocks & Minerals (1938) reported arsenopyrite from Devil’s Den.

Chalcopyrite CuFeS2 was reported by Clapp & Ball (1909) from Devil’s Basin.

Galena PbS was reported by Clapp & Ball (1909) from Devil’s Basin.

Pyrite FeS2 was reported by Cushing (1826), McDaniel (1884), Boston Mineral Club (1949) and Krumm & Teichman (1958). Small crystals were also found at Devil’s Den in the present study.

Pyrrhotite Fe1-xS was found as magnetic grains on specimens from Devil’s Den at the Harvard Mineralogical Museum, in the Florian Woitowicz (1921-2010) collection (Carl Francis, pers. comm., 2011).

Sphalerite (Zn,Fe)S was listed by Krumm & Teichman (1958).

Sulfates

Gypsum CaSO4 · 2H2O was listed by Boston Mineral Club (1949).

Oxides

Brucite var. "Nemalite" Mg(OH)2 was listed by Dana & Brush (1868) from “Newburyport,” and by the Essex Institute (1885). Brucite typically occurs as an alteration product of periclase (MgO) in marbles. These reports need modern verification.

Chromite Fe2+Cr3+2O4 was reported from Devil’s Basin by Sears (1894, 1905) as chromic iron. Sears believed the deposits were an altered peridotite rather than an altered magnesian limestone. However Clapp (1921) says the sedimentary origin of the deposits is “indubitable.”

Silicates

Actinolite ◻Ca2(Mg4.5-2.5Fe0.5-2.5)Si8O22(OH)2 was found as small bladed crystals in calcite, associated with diopside (NEW, this study, 2015)

Diopside CaMgSi2O6 was reported by Clapp & Ball (1909), and diopside is present in specimens from the collection of Florian Woitowicz (1921-2010) acquired by the Harvard Mineralogical Museum. Noted as colorless to pale green micro-crystals in calcite (this study, 2015).

Epidote (CaCa)(AlAlFe3+)O[Si2O7][SiO4](OH) was reported by Cleaveland (1816); by Robinson (1825) as “large crystals in fissures in ‘amorphous garnet’ ”; and by Hitchcock (1833), Dana (1844, 1854), Dana & Brush (1868), Dana (1892) and Boston Mineral Club (1949). No data were seen indicating whether the mineral species reported in these references is epidote or another member of the epidote group such as clinozoisite.

Garnet Group: (Grossular: Ca3Al2(SiO4)3 and Andradite Ca3Fe3+2(SiO4)3). Massive garnet is common at Devil’s Den but crystals are rare. Reports of massive garnet were made by Warren and Jackson (1813), Cleaveland (1816), Robinson (1825), Cushing (1826), Hitchcock (1833), Dana (1844, 1854), Essex Inst. (1858), Dana & Brush (1868), Balch (1869), Nason (1876), McDaniel (1884), Essex Inst. (1885), Sears (1894), and Clapp & Ball (1905, 1909). Clapp and Ball (1909) identified the massive brown garnet as andradite. Boston Mineral Club (1949) listed andradite, and Krumm & Teichman (1958) reported grossular under its old name, grossularite. Crystals collected by John Chipman in 2009 (see photo, this article) were analyzed (SEM-EDS, this study) and determined to be grossular.

Olivine (probably forsterite,Mg2SiO4) was seen in thin section by Sears (1905), as grains partially to completely altered to serpentine.

Opal var. “Hyalite” SiO2 · nH2O was found in 2011 as fluorescent coatings on specimens from Devil’s Basin (this study).

Phlogopite KMg3(AlSi3O10)(OH)2 was found as grayish green foliated masses and crude crystals at Devil's Den. Uncommon. Analyzed, SEM-EDS. (NEW, this study, 2016)

Quartz SiO2 was listed by Krumm & Teichman (1958) as occurring as casts after calcite.

Serpentine Group: Massive Serpentine includes Antigorite Mg3(Si2O5)(OH)4 and Lizardite Mg3(Si2O5)(OH)4. Serpentine is very common at both quarries. Massive serpentine, some of it gem-quality (precious or noble serpentine) was reported by Warren and Jackson (1813), Cleaveland (1816), Phillips (1819), Nuttall (1822), Vanuxem (1823), Robinson (1825), Cushing (1826), Literary and Historical Society of Quebec (1829), Hitchcock (1833), Finch (1833), Dwight (1833), Newhall (1835), Feuchtwanger (1838), Trimmer (1841), Coffin & Bartlett (1845), Felton (1854), Hunt (1854), Essex Inst. (1858), Woods (1860), Perkins (1864), Barden (1864), Balch (1869), Nason (1876), McDaniel (1884), Whitney & Wadsworth (1884), Essex Inst. (1885), Crosby (1888), Dana (1892), Sears (1894, 1905), Ladd (1894), Clapp & Ball (1905, 1909), Clapp (1921), Bartsch (1941), Boston Mineral Club (1949), Krumm & Teichman (1958) and Sinkankas (1959).

Julien (1914) interprets chemical analyses of Newbury serpentine as showing antigorite with up to 22% deweylite etc. Deweylite is not considered a valid mineral, but is a mixture, primarily of lizardite and stevensite: (Ca,Na)xMg3-x(Si4O10)(OH)2. Deweylite was also listed by Hitchcock (1833).

Varietal names which have been used for serpentine from Newbury include picrolite: Sears (1894, 1905) and Boston Mineral Club (1949); picrosmine, marmolite and Baltimorite by Sears (1894, 1905); and retinalite (Essex Inst., 1885). Serpentine pseudomorphs after augite, hornblende, and olivine were seen in thin section by Sears (1894, 1905). Verde antique (a marble consisting of green serpentine with white carbonate minerals) was reported by Hitchcock (1833, 1841), Balch, (1869), McDaniel (1884), Ladd (1894), Sanford & Stone (1914) and Sinkankas (1959).

Barden (1864) exhibited an elegant vase made of serpentine by a Mr. Osgood of Newburyport.

Serpentine Group: Chrysotile Mg3(Si2O5)(OH)4 ("asbestos; "amianthus"; "rag-stone"). Chrysotile is commonly seen at Devil’s Den. Reported by Belknap (1780) as asbestos, Morse (1789, 1792) as asbestos, Parish (1807) as asbestos, Warren and Jackson (1813) as asbestos ligniform and amianthus, Cleaveland (1816) as asbestus [sic] and amianthus, V.P. (1816) as asbestos on Kent Island, B.P. (1819) as asbestus [sic], Nuttall (1822) as amianthus, Robinson (1825) as “amianthus and the common variety of asbestos,” Cushing (1826) as asbestos, Literary and Historical Society of Quebec (1829) as "serpentine variety amianthus", Hitchcock (1833) as amianthus, Dwight (1833) as amianthos [sic] and asbestos, Newhall (1835) as asbestos and amianthos [sic], Finch (1833) as asbestos, Coffin & Bartlett (1845) as asbestos and amianthus, Felton (1854) as rag-stone, Dana (1854) as chrysolite [sic], Essex Inst. (1858) as asbestos, Woods (1860) as asbestos and amianthus, Perkins (1864) as asbestos, Barden (1864) as "asbestos or amianthus", Dana & Brush (1868) as chrysotile, Balch (1869) as asbestos, Meader (1869) as “asbestos and amianthus, a variety of hornblende” Lund (1873) as asbestos, Nason (1876) as chrysolite [sic] and asbestos and amianthus, Crosby (1880, 1888) as chrysotile, McDaniel (1884) as “asbestiform serpentine, or chrysotile,” Essex Inst. (1885) as chrysolite [sic], Dana (1892) as chrysotile, Sears (1905) as chrysotile, Boston Mineral Club (1949) as chrysotile and Krumm & Teichman (1958) as chrysotile.

Sodalite Erroneously reported; Listed by Gleba (1978). The source of this report is not known; there may have been a mix-up with a specimen from Salem.

“Steatite” A massive variety of talc, Mg3Si4O10(OH)2. Listed by Perkins (1864). Doubtful.

Titanite CaTi(SiO4)O was found as colorless to pale yellowish tan micro-crystals in calcite, associated with grossular (NEW, this study, 2015)

Tremolite ◻Ca2Mg5(Si8O22)(OH)2. The white massive mineral with a bladed habit found at Devil’s Den was identified as tremolite until Wadsworth (1877) proved the mineral was actually wollastonite. Early reports of tremolite were provided by Warren and Jackson (1813), Cleaveland (1816), Robinson (1825), Cushing (1826), Comstock (1832), Hitchcock (1833), Coffin & Bartlett (1845), Essex Inst. (1858) and Balch (1869). Sears (1894) was the last to report it. Frondel (1988) called the asbestos at Devil’s Den “tremolite” but this is questionable. [See the entry for Serpentine Group: Chrysotile.] Tremolite remains unverified.

Vesuvianite Ca19Fe3+Al4(Al6Mg2)(◻4)◻[Si2O7]4[(SiO4)10]O(OH)9 was first reported by Crosby (1888) and later listed by Kunz (1890), Dana (1892) and Bartsch (1941). Sears (1894) at first doubted that the massive brown mineral studied by Crosby was vesuvianite believing it to be garnet, but later (1905) he accepted the identification. A massive brown mineral from Devil’s Basin found in the present study may be vesuvianite.

Wollastonite Ca3(Si3O9) was reported by Wadsworth (1877), Crosby (1880, 1888), McDaniel (1884), Essex Inst. (1885), Clapp & Ball (1905, 1909), Bartsch (1941), Boston Mineral Club (1949) and Krumm & Teichman (1958). Evans (1945) identified a white fibrous mineral from Devil’s Den as wollastonite via optical and X-ray methods. Gosse (1969) says wollastonite is occasionally cut and polished for collectors. The mineral is common in both quarries. ■

Conclusion

Devil's Den and Devil's Basin have somehow survived for centuries, their atmosphere of mystery remaining intact. Hidden in thick woods and underbrush, these two ancient quarries are in need of modern mineralogical investigation, as the list of species in this article is certainly not complete. At the same time, both sites are in need of protection (especially Devil's Den) so that they may be preserved for the benefit of future generations.

REFERENCES

- B. P. (1819) [full name not recorded]. An Essay on Asbestus (Journal of the Times, Baltimore, January 30, 1819; Originally in the Newburyport Herald).

– Balch, David (1869). List of Minerals Collected in Essex County, and Arranged in the County Collection of the Peabody Academy of Science (First Annual Report of the Trustees of the Peabody Academy of Science).

– Baker, Emerson W. (2007). The Devil of Great Island: Witchcraft and Conflict in Early New England (NY: Palgrave Macmillan).

– Barden, S. (1864). [Field Meeting at Devil’s Den, September 16, 1864] (Proceedings of the Essex Institute, Vol. 3, p. 51.)

– Bartsch, Rudolf (1941). New England Notes (Rocks & Minerals 16:56).

– Beard, Robert (2008). Enter the Devil’s Den (Rock & Gem v. 38, no. 8).

– Belknap, Jeremy (1780). Letter to Ebenezer Hazard: Dover, August 28, 1780, in Belknap Papers (Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. II – Fifth Series, Boston, 1877).

- Bentley, William (1813). Diary entry for September 28, 1813, in The Diary of William Bentley, Volume 4, January, 1811 - December, 1819 (Salem, MA: The Essex Institute, 1914) p.202-203.

– Blake, Euphemia Vale (1854). History of Newburyport.

– Boston Mineral Club (1949). The Newbury–Newburyport Field Trip (Boston Mineral Club newsletter, March 1949).

– Clapp, C. H. and W. G. Ball (1905). Geology of the Newbury Mining District (MIT Thesis).

– Clapp, C. H. and W. G. Ball (1909). The Lead-Silver Deposits at Newburyport, Massachusetts and Their Accompanying Contact-Zones (Economic Geology, 4(3):239–250).

– Clapp, Charles H. (1921). The Geology of the Igneous Rocks of Essex County, Mass. (USGS Bulletin 704).

– Cleaveland, Parker (1816). An Elementary Treatise on Mineralogy and Geology (Boston: Cummings and Hilliard), p.153.

– Coffin, Joseph and Bartlett, Joseph. (1845). A sketch of the history of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury from 1635 to 1845. (Boston: Samuel G. Drake).

– Comstock, John Lee (1832). An Introduction to Mineralogy.

– Crosby, William O. (1880). Contributions to the Geology of Eastern Massachusetts. (Occasional papers of the Boston Society of Natural History, Volume 3).

– Crosby, William O. and Greely, James T. (1888). Vesuvianite from Newbury, Mass. MIT Technology Quarterly, vol. 1, pp. 407–408.

– Currier, John J. (1896). “Ould Newbury”: Historical and Biographical Sketches (Boston: Damrell and Upham), pp. 421–423.

– Cushing, Caleb (1826). The History and Present State of the Town of Newburyport (Newburyport: E. W. Allen), p. 38.

– Dana, Edward S. (1892). A System of Mineralogy, 6th edition.

– Dana, James D. (1844). A System of Mineralogy, 2nd edition.

– Dana, James D. (1854). A System of Mineralogy, 4th edition.

– Dana, James D. and Brush, George J. (1868). A System of Mineralogy, 5th edition.

– Daniels, Elizabeth (1931). Devil’s Den (Rocks & Minerals 6:28).

– De Alcedo, Antonio; George Alexander Thompson, Aaron Arrowsmith (1812). The geographical and historical dictionary of America and the West Indies, p. 232.

– Dwight, Theodore (1833). Gazetteer of the United States of America (Hartford, Conn.: Edward Hopkins).

– Essex Institute (1858). Field meeting at Newburyport (Proceedings of the Essex Institute, Vol.1, p. 277).

– Essex Institute (1885). Report of the Annual Meeting Held Monday, May 18, 1885. [Description of field trip of Oct. 13, 1884].

– Evans, Howard T. (1945). Identification of Minerals (Boston Mineral Club newsletter, Feb. 1945).

– Ewell, John (1904). The Story of Byfield: A New England Parish (Boston: George E. Littlefield), p. 194.

– Felton, C. C. (1854) in A Report on the Proceedings on the Occasion of the Reception of the Sons of Newburyport, July 4, 1854 (Newburyport, MA: Moses H. Sargent).

– Feuchtwanger, Lewis (1838). A Treatise on Gems: In Reference to Their Practical and Scientific Value (NY: A. Hanford), p. 148.

– Finch, I. (1833). Travels in the United States of America and Canada (London: Longman et al.).

– Frondel, Clifford (1988). Benjamin Franklin’s purse and the early history of asbestos in the United States (Archives of Natural History, Vol. 15, pp. 281–287).

– Gosse, Ralph (1969). A Catalogue of Massachusetts Gemstones – Essex County (Part Two) (Rocks and Minerals 44:198).

- Hazard, Ebenezer (1788). Letter to Jeremy Belknap, May 10, 1788. (Collections of the Mass. Historical Society, vol. 3, 5th series, 1877). A request for 3–4 lbs of “asbestos.”

– Hitchcock, Edward (1833). Report on the Geology, Mineralogy, Botany, and Zoology of Massachusetts.

– Hitchcock, Edward (1841). Final Report on the Geology of Massachusetts, Vol. 1.

– Hunt, T. S. (1854). On some of the crystalline limestones of North America [abstract] (American Journal of Science, 2nd series, vol. 53, Sept. 1854.).

– Julien, Alexis A. (1914). The Genesis of Antigorite and Talc (Annals of New York Academy of Sciences 24:23–38).

– Krumm, Jerry and Teichman, Chester (1958). [Field Trip Notice, Nov. 9, 1958] Chipman Mine and Devil’s Den (Boston Mineral Club newsletter, Nov. 1958).

– Kunz, George F. (1890). Gems and Precious Stones of North America.

– Ladd, George E. (1894). The building stone collection (Report of the Massachusetts Board of World’s Fair Managers).

– Literary and Historical Society of Quebec (1829): Catalogue of the Mineralogical Collection in Transactions of the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, Vol. 1.

– Lunt, George (1873). Old New England Traits (Cambridge: Riverside Press), pp.15–16 (“rag-stone” = asbestos).

– McDaniel, B.F. (1884). Geology and Mineralogy of Newbury in Bulletin of the Essex Institute, volume XVI, p. 163-169.

– Meader, J. W. (1869). The Merrimack River (Boston: B.B. Russell).

- Morse, Jedidiah (1789). The American Geography, 1st ed. (Elizabeth Town, NJ: printed by Shepard Kollock for the author), p. 183.

– Morse, Jedidiah (1792). The American Geography, 2nd ed. (London: John Stockdale), p. 183.

– Nason, Elias (1876). A Gazetteer of Massachusetts. (Boston: B.B. Russell).

– Newhall, James Robinson (1835). The Essex Memorial for 1836 (Salem, MA: Henry Whipple).

– Nuttall, Thomas (1822). Observations and Geological Remarks on the Minerals of Paterson and the Valley of Sparta, in New Jersey (The New York Medical and Physical Journal, Vol. 1., p. 197.).

– Perkins, H. C. (1864). [Field Meeting at Devil’s Den, September 16, 1864] (Proceedings of the Essex Institute, Vol. 3, p. 51).

– Parish, Elijah (1807). A Compendious System of Universal Geography (Newburyport, MA: Thomas & Whipple), p. 45.

– Phillips, William (1819). An Elementary Introduction to the Knowledge of Mineralogy, 2nd edition (London: 1819), p. 77.

– Robinson, Samuel (1825). A Catalogue of American Minerals, With Their Localities, p. 63.

– Rocks & Minerals (1938). 13:183.

– Sanford, Samuel and Stone, Ralph W. (1914). Useful Minerals of the United States (USGS Bulletin 585).

– Sears, John Henry (1894). Geological and Mineralogical Notes, No. 9 in Bulletin of the Essex Institute, volume XXVI.

– Sears, John Henry (1905). The Physical Geography, Geology, Mineralogy and Paleontology of Essex County.

– Sewall, Samuel (1697). Diary, vol. 1, p.458. in Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. 5, 1878.

– Sinkankas, John (1959). Gemstones of North America, Vol. 1, p.544.

– Skinner, Catherine W.; Ross, Malcolm; and Frondel, Clifford (1988). Asbestos and Other Fibrous Materials (NY: Oxford University Press).

– Trimmer, Joshua (1841). Practical Geology and Mineralogy (London: John W. Parker).

– V.P. [initials only} (1816). Asbestos (Baltimore, MD: Niles Weekly Register, Vol. 10, p. 400; August 10, 1816) V.P. was the editor of a Richmond newspaper.

– Vanuxem, Lardner (1823). On the Marmolite of Mr. Nuttall (Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Vol. 3, pp.129–135).

– Wadsworth, M. Edward [1877]. On the So-Called Tremolite of Newbury, Mass. (Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History 19:251, 1878).

- Warren, John Collins; and Jackson, James, eds. (1813). [Review of] "Address delivered before the Society for the Promotion of Useful Arts at the Capitol in the City of Albany, by Theodoric Romeyn Beck, one of the Counsellors of the Society &c."; To which is added a catalogue of Minerals in Massachusetts, New England Journal of Medicine, 2(2):183-193, April, 1813.

– Whitney, J. D and Wadsworth M. E. (1884). The Azoic System and Its Proposed Subdivisions (Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Geological Series v.1).

– Whittier, John Greenleaf (1859). The Double-Headed Snake of Newbury” (Atlantic Monthly, March 1859).

– Woods, Leonard (1859). Address of the Life and Character of Parker Cleaveland, LL.D. (Portland: Brown & Thurston), p. 32.

Article has been viewed at least 31412 times.