Charles Ottley Groom Napier (an eccentric British collector)

Last Updated: 11th Oct 2023By David Carter

Charles Ottley Groom Napier, also known as C.O.G. Napier, FGS FLS (14th May 1839 - 17th January 1894), was a natural historian and geologist. He was a collector of fossils, minerals, and plants, as well a writer on various subjects, including ornithology and vegetarianism. He was also an early proponent of British Israelism. However, sad to say, he is probably more well known for his eccentric claims of ancestry. It has been suggested the print below, which appears on page 301 of his 1869 book “Tommy Try & What he did in Science”, is actually a portrait of Charles Ottley Groom Napier himself.

He was born on 14th May 1839 on the island of Tobago in the Caribbean at Merchiston, a small place approximately 24 km (15 mi) from Tobago's capital Scarborough, eight and a half months after the premature death of his father Charles Edward Groom (1815-1838), a very wealthy sugar plantation owner or manager, and his wife, Ann Napier (1815-1895). He would later (around 1865) add Napier (his mother’s maiden name) to his name, becoming Charles Ottley Groom Napier. Moving to England with his highly protective mother Ann Napier, he lived in Exeter, Devon as a young boy. After Charles caught whooping cough aged 9 they moved to Exmouth a few miles to the south in order to be by the seaside. As he continued for several years to suffer from delicate health his mother subsequently let their house in Exmouth and both she and Charles moved into lodgings when he was 11 years old. At first they resided at Budleigh Salterton, a town five miles east along the coast, but they then moved a little further inland to Honiton which had been recommended for its healthiness. However, due to the damp and rain, they later moved to a less wooded district of Devon and lived first at Devonshire Buildings in Weymouth and then to more commodious lodgings near the sea in a more central part of Weymouth town. Charles was a sickly child by all accounts, with precocious interests in natural history, the sciences, and antiquarianism. Around the age of 15, he and his mother moved to Lewes in East Sussex. In fact, Charles continued to live with his mother until his death. He is recorded in 1865 as living in the port of Bristol. In 1872 he was shown to be residing at 20 Maryland Road in London and in 1878 he resided at 18 Elgin Road, Harrow Road, London.

Stemming from his early interests in natural history he subsequently obtained a degree in geology and later became a member of the Geological Society of London. He was nominated to the Linnean Society of London and also joined as a Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society. He was elected a Fellow of the Geological Society of London on 24th May 1865, although he resigned in 1878, possibly over the publication of his “Burlington House” magazine (the cover of this implied that it had been produced under the auspices of the Geological Society of London, which it had not)!

In January 1870, Charles Ottley Groom Napier (from now on I shall just refer to him as Napier) wrote to Charles Darwin and the transcript of that letter is:

Henry Peter Brougham died in 1868 and it is most doubtful whether Napier personally knew Brougham or even whether Brougham wrote the preface to “The Book of Nature and the Book of Man” by Napier. Also, there are no copies of “The Book of Nature and the Book of Man” to be found in the Darwin Libraries at either Cambridge University or Down House, Kent.

In his 2004 book, “The Heretic in Darwin’s Court: The Life of Alfred Russel Wallace”, author Ross A. Slotten writes about English physicist and parapsychologist William Fletcher Barrett who had became interested in the paranormal in the 1860s after having an experience with mesmerism. Barrett believed that he had been witness to thought transference and by the 1870s he was investigating poltergeists. In September 1876, Barrett published a learned paper called “On Some Phenomena Associated with Abnormal Conditions of the Mind” outlining the result of these investigations. In the same year he was presenting his findings for the Anthropological Department of the British Association for Advancement of Science to around 1,200 people:

Eccentric ancestry claims

From the late 1860s, bizarrely and for seemingly unknown reasons, Napier began to assume a series of self-aggrandising and ever grander titles (all entirely imaginary). A 200 plus page document was produced setting out the pedigree of himself and his mother, who assumed (or was given by her son) the title of Duchess of Mantua, Montferrat and Ferrara. A copy is in the British Library, and an online version is available from the National Library of Scotland - a link is in the references section at the bottom of this article. Napier started to style himself as the Prince (Duke) of Mantua and Montferrat with subsidiary titles as the Prince of Ferrera, Nevers, Rethel, and Alençon; Baron de Tobago; and Master of Lennox, Kilmahew, and Merchiston. By the time of his death he had adopted yet another name, Charles Bourbon d’Este Paleologus Gonzaga.

The House of Gonzaga is actually an Italian princely family that ruled Mantua in Lombardy, northern Italy from 1328 to 1708 (first as a captaincy-general, then margraviate, and finally duchy. They also ruled Monferrato in Piedmont and Nevers in France, as well as many other lesser fiefs throughout Europe. The family includes a saint, twelve cardinals, and also fourteen bishops. Two proper Gonzaga descendants became empresses of the Holy Roman Empire (Eleanora Gonzaga) and Eleonora Gonzaga-Nevers), and one became queen of Poland (Marie Louise Gonzaga).

The locations for all his assumed titles are as follows:

Mantua is a city and municipality in Lombardy, Italy and capital of the province of the same name.

Montferrat is part of the region of Piedmont in northern Italy.

Ferrera is a municipality in the Viamala Region in the Grisons, Switzerland. Nevers is the prefecture of the Nièvre Department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté Region in central France.

Rethel is a commune in the Ardennes Department in northern France.

Alençon is a commune in Normandy, France, capital of the Orne Department.

Tobago is an island within the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, located 22 miles northeast of the mainland of Trinidad and southeast of Grenada, about 99 miles off the coast of northeast Venezuela.

The Lennox is a region of Scotland centred on The Vale of Leven, including its great loch: Loch Lomond.

Kilmahew Castle is a ruined castle located just north of Cardross, in the area of Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

Merchiston is a residential estate in the southwest of Edinburgh, Scotland.

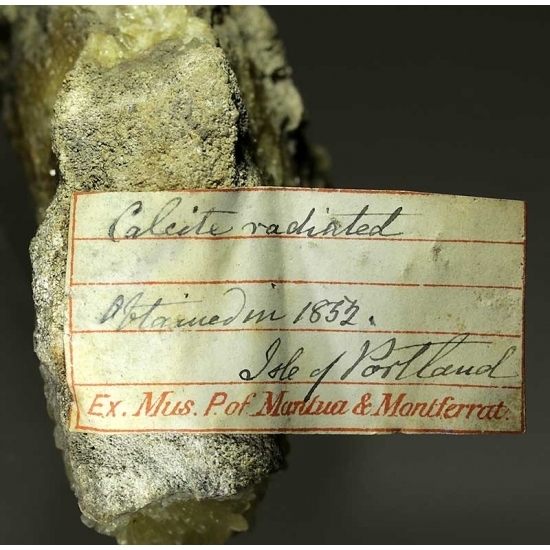

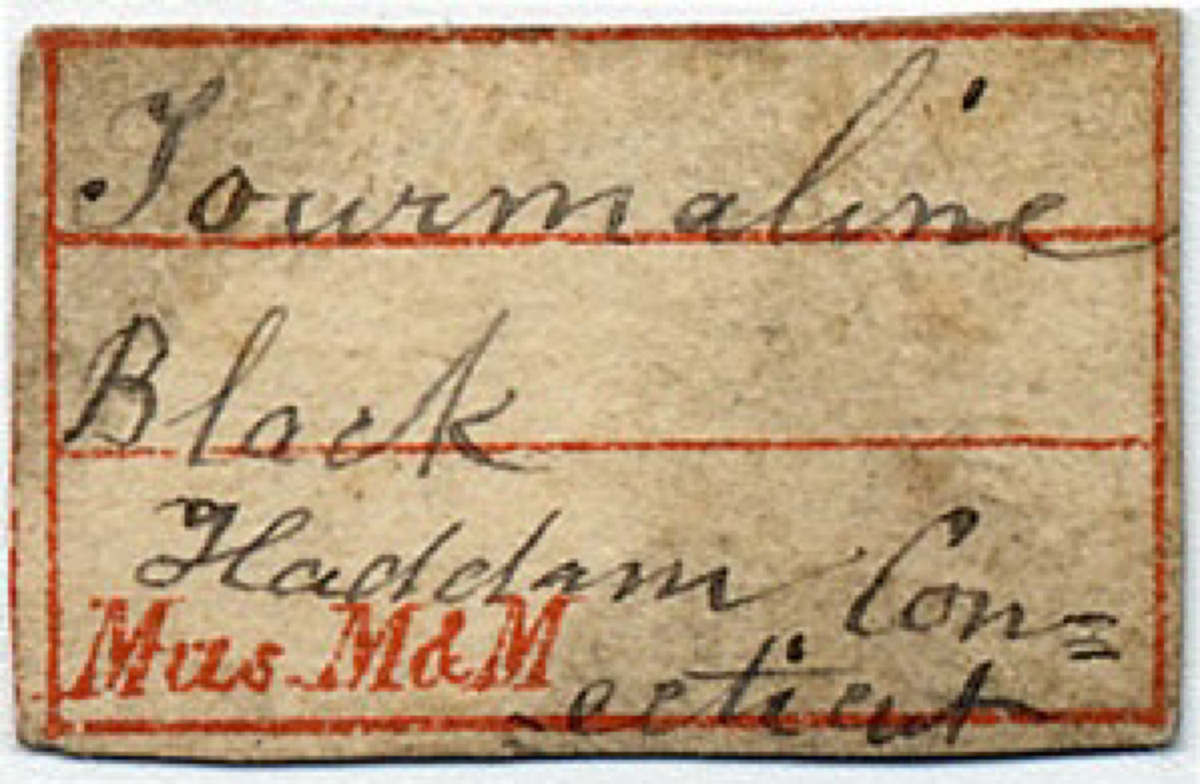

Napier clearly had a plan in his mind and was without doubt trying to advance his prestige, and naively attempting to spread his comparatively diminutive influence far and wide. He grew obsessed with his genealogy and insisted that he was descended from various European royal families and that he could trace his lineage all the way back to the Biblical King David. He worked with the genealogist John O’Hart and claimed that he could trace his ancestry to various European royal bloodlines or nobles through his mother Ann Napier. Works from John Riddell (a 19th century peerage lawyer) were published in 1879 attempting to link her to the Duchess of Mantua and Montferrat in Italy and the Scottish Clan Napier. These claims however were dismissed as a complete fabrication by most genealogists. Consequently, Napier’s academic reputation was heavily besmirched by scientists because his mineral collection was registered in the name of “Ex. Mus. P[rince] of Mantua & Monferrat”.

On 24th March 1879, Napier held a banquet for 7,000 guests in a specially-constructed pavilion at Greenwich in London, the walls of which were hung with 700 illuminated leaves of vellum illustrating his (purported) pedigree. Only vegetarian food was served, along with a drink of his devising that he called “curry champagne” made from a mixture of curry powder and ginger beer. There is no record of who, or how many, turned up, but apparently Napier himself was too ill to attend the festivities!

Napier never retracted his claims of ancestry and when he died of long-standing cardiac disease on 17th January 1894 his death was registered in London as that of “Charles de Bourbon d'Este Paleologues Gonzaga, prince of Mantua and Montferrat”. When his mother died a year later, having assumed the title of Dowager Duchess of Mantua, she was registered under the name Ann de B.D.P. Gonzaga. In October 1895, the Horniman Museum in Forest Hill, south London, bought a significant amount of Papua New Guinea material from the Mantua collection at an auction.

In one of his later volumes of work entitled; “Works of H.R. and M.S.H. the Prince of Mantua and Montferrat, Prince of Ferrara, Nevers, Réthel, and Alençon. London” (Dulau and Co, 1886), Napier had prefaced the book with sixty-four pages of fictitious rave reviews and testimonials provided by such illustrious individuals as Victor Hugo (“miraculous”), Michael Faraday (“a marvel”), Anthony Trollope (“too much for this wicked world”), Elizabeth Barret Browning, Charles Darwin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Abraham Lincoln, and Pope Pius IX. All of these reviews were fraudulent, all of them invented by Napier. However, conveniently for him, none of these people were available to dispute the attributions since they were all recently deceased!

Prize medals

He also decided he was going to reintroduce a “Mantua & Montferrat Medal Fund”, which he claimed had been created by his ancestor Lodovico Gonzaga in the 14th century to confer recognition on men eminent in arts, letters and science! Harking back to the genuine medals created in Renaissance Italy by the nobility of Mantua and other city states, Napier initiated production of a gilded bronze “Prince of Mantua and Montferrat’s Prize Medal” to support his assumed lineage. A total of twenty-four medals were issued by him in 1879 and he bestowed them (by post!) on various eminent men - a link to the full list is in the references section below.

The medals were sent to the recipients, who were instructed, via an accompanying letter, to acknowledge receipt upon delivery and write back to Napier with a photograph of themselves with the medal. He collated and recorded the replies, and claimed that all the recipients had replied as instructed by 1883. The medals were all identical except for the name of the recipient; some including British statesman, politician and Prime Minister (although not at the time the medal was issued) William Gladstone refused the “honour”; British botanist and explorer Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin’s closest friend) received his medal for “geographical botany”. His reply to the “Prince” was sent from the Royal Botanical Gardens Kew, where Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker was Director, on the 4th October 1882. Hooker was said to have accepted the medal with “guarded courtesy”. Mention of it is noticeably absent from the extensive list of medals, honours and awards that were received by Hooker between 1839 and 1908; A medal was also sent to British biologist, comparative anatomist and palaeontologist Sir Richard Owen (generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils). This medal is now held in the Natural History Museum, London; Another medal was sent to the British writer, philosopher, art critic, and polymath John Ruskin (who wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany, and political economy). Ruskin replied enthusiastically to Napier from his home in Herne Hill London on 2nd April 1882, but did not include a photograph. His medal is in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Regarding the details that were shown on the medals, the obverse features a profile portrait of an as-yet unidentified man and the reverse lists claimed past recipients; Raphael, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Dante, Tasso, Columbus, Ariosto, Galileo, Copernicus, Racine, Molière, Cervantes, Milton, Shakespeare, Newton, Napoleon, and Cuvier. Napier was also included between Shakespeare and Newton!

At the 1879 banquet mentioned earlier, it is understood that the great and the good were going to be presented with medals there as well (the reverse had a space for naming), but for some unknown reason this never came about and unnamed medal examples remain extremely rare.

British Israelism

Napier read a paper to the London Anthropological Society in 1875, entitled "Where are the Lost Tribes of Israel". He believed that the British descended from the Ten Lost Tribes and was a personal friend of Edward Hine who was an influential proponent of British Israelism in the 1870s and 1880s. Hine went as far as to conclude that "It is an utter impossibility for England ever to be defeated. And this is another result arising entirely from the fact of our being Israel." Hine departed England for the United States in 1884, where he promoted the idea that Americans were the lost tribe of Manasseh, whereas England was the lost tribe of Ephraim.

British Israelism (also called Anglo-Israelism) is the belief that people of Western European descent, particularly those in Great Britain, are the direct lineal descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. The concept often includes the belief that the British Royal Family is directly descended from the line of King David.

British Israelism as an established movement traces itself back to the 17th century. Adriaan van der Schrieck (1560–1621) a Flemish language researcher in 1614 wrote, “...the Netherlanders with the Gauls and Germans together in the earliest times were called: Celts, who are come out of the Hebrews”.

In a 2014 book called “The Evolutionist: The Strange tale of Alfred Russel Wallace”, author Avi Sirlin writes about a presentation at the British Association for Advancement of Science in Glasgow on 12th September 1876, where Napier is mentioned.

Literature

Napier wrote prolifically on the natural sciences too and, for much of his career, he was a conventional and well respected author. He published numerous learned articles and his books included:

“The Food, Use, and Beauty of British Birds: An Essay : Accompanied by a Catalogue, of All the British Birds.” (1865)

“Miscellanea Anthropologica, or Illustrations of Races: Three Essays Reprinted From the Anth[Ropological] Jour[Nal], Etc.” (1867)

“Variations in the Colour, Form and Size of the Eggs of Birds” (1868)

“The Book of Nature and the Book of Man: In Which Is Accepted As the Type of Creation, the Microcosm, the Great Pivot On Which All Lower Forms of Life Turn.” (1870)

“Vegetarianism in the Bible” (1879)

“Lakes and Rivers [Natural History Rambles]” (1879); this is probably the most commonly encountered Napier work these days.

“Works of H.R. and M.S.H. the Prince of Mantua and Montferrat, Prince of Ferrara, Nevers, Réthel, and Alençon” (1886)

Napier even wrote an autobiographical book, called “Tommy Try And What He Did In Science” (1869), engraved with forty-six illustrations. I consider myself fortunate to own a 1st edition of this extremely rare book, in addition to owning a 2nd edition (1880) of Lakes and Rivers [Natural History Rambles], both in great condition.

Additionally, Napier contributed significantly to a book by French scientist and writer Louis Figuier called “The Ocean World: Being a Description of the Sea and its Living Inhabitants” (1868). Napier rearranged the whole of the Mollusca section with the chapters on conchology being revised and enlarged by him for the 1869 edition. A link to a free copy of the full book (Project Gutenberg eBook) is in the references section below.

Various collections

As a prominent collector, Napier was voracious and he acquired a large number of mineral, fossil, and plant specimens from around the world. Many of these were later sold to the Natural History Museum, London. He also amassed a big collection of miscellaneous prints.

Eventually the mineral portion of his collection was purchased by the German mineral dealer Friedrich Krantz, taken to Bonn, and dispersed.

Napier bought the personal collection of fossils from James Tennant, who was a British mineralogist and mineralogist to Queen Victoria. The Tennant collection was later purchased by Robert Damon and sold to the Western Australian Museum in Perth where it remains today.

A large part of his herbarium is currently preserved in the United Kingdom at Bolton Museum, Greater Manchester, England. A link in the references section below provides a list of the herbaria specimens collected by Napier.

In 1878, Napier sold 651 prints to the British Museum. These can be viewed through their online collection - a link is in the references section below.

Mineral specimens

Mindat members might be familiar with or maybe even have in their possession, labelled or otherwise, old mineral specimens of Charles Ottley Groom Napier. Notwithstanding his eccentricities and somewhat poorly considered reputation I consider myself lucky to own several of his labelled specimens; a calcite twinned scalenohedron crystal specimen from Somerset in England, a rhombohedral calcite cleavage specimen from Cornwall in England, and a specimen of plagioclase (oligoclase) crystals perched on a granitoid matrix from Switzerland (shown below). Napier specimens do occasionally appear on the market and the original labels on them are quite distinctive with their thin red lines/borders and cursive writing. The labels often include “Mus. M. & M.” printed in red upon them, or the much rarer “Ex. Mus. P. Mantua & Montferrat.” (also printed in red). Seemingly, more often than not locations given for specimens are not very accurate or can be rather vague to say the least. Napier was also in the habit and well known for making up localities to "increase" the rarity and value of his specimens!

Other examples of minerals with labels:

Examples of labels only:

Conclusion

His youthful enthusiasm for more traditional sciences, such as biology and chemistry, was somewhat dampened in later years and nowhere is this better illustrated than in the small extract from his 1869 book “Tommy Try And What He Did In Science”, as shown below.

However, he did retain huge respect and a great deal of enthusiasm about the life and works in particular of the German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science, Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt, who died in 1859. Napier also took intense delight in the literary works of William Shakespeare and in later years he developed an avid interest in the pseudoscience of phrenology which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.

Napier lived at a time called the Age of Enlightenment (also known as the Age of Reason or simply Enlightenment), when the intellectual and philosophical movement dominated the world of ideas in Europe. Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies, which had largely replaced universities as centres of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were also the backbone of the maturation of the scientific profession. Another important development was the popularisation of science among an increasingly literate population. A genre that greatly rose in importance was that of scientific literature. Natural history in particular became increasingly popular among the upper classes. Knowledge was based on experimentation, which had to be witnessed to provide proper empirical legitimacy. However, not just any witness was considered to be credible: “Oxford professors were accounted more reliable witnesses than Oxfordshire peasants’”. Two factors were taken into account: a witness's knowledge in the area and a witness's “moral constitution”. In other words, only the civil society and people of high standing were legitimately considered worthy. Social status, ladder climbing and one-upmanship all played an important role in determining a person’s place within society. It was also probably fairly easy to find yourself “backing the wrong theory” during a period when so much was new and often fast changing as well!

I suspect that Charles Ottley Groom Napier was ultimately just doing what he thought was best in his own mind and he was attempting to advance himself by whatever means he could in order to find a worthy place in the increasingly competitive, sometimes pretty ruthless and unsparing, dog-eat-dog environment that he found himself in. My personal view is that he was a clever man, albeit with obvious flaws in his character, and sometimes he found himself out of his depth. He also made a few wrong choices along the way of life perhaps, as is often the case! He seems to have done no harm and there is evidence that he did make a contribution (however large or small is open to much debate) in the worlds of both literature and science. Ultimately, it seems he secured a place in the annals of history and will be remembered for the small part he played in the 19th century.

The story of Charles Ottley Groom Napier’s life has been covered by others, including Brian William Fox FLS (1929-1999) in the 1993 edition of The Linnean, no. 9 (2), pp. 26-28. Many sources cast doubt on the man, his works and abilities.

https://ca1-tls.edcdn.com/Linnean-9-2-1993.pdf

The Pedigree of Her Royal and Most Serene Highness THE DUCHESS OF MANTUA, MONTFERRAT, AND FERRARA; Nevers, Rethel, and Alengon; Countess of Lennox, Fife, and Menteth; Baroness of Tabago;

In which is traced her Descent from King David, the Houses of Gonzaga, Paleologus, Este, Bourbon, Lennox, Napier, etc.

https://digital.nls.uk/histories-of-scottish-families/archive/95659015#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=8&xywh=-150%2C-1%2C2798%2C3201

Full list of Prince of Mantua medal recipients as given in the

‘Pedigree of Her Royal and most serene Highness the Duchess of

Mantua, Montferrat, and Ferrara’ (1885).

https://ca1-tls.edcdn.com/MantuaMedalRecipients.pdf

Project Gutenberg eBook (free copy) “The Ocean World: Being a Description of the Sea and its Living Inhabitants” (1869), by Louis Figuier with revisions by Charles Ottley Groom Napier.

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/47626/pg47626-images.html

Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland (label examples and search for specimens collected Charles Ottley Groom Napier.

https://herbariaunited.org/collector/11109/

British Museum - Charles Ottley Groom Napier print collection. Click on related objects after following the link.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG246194

He was born on 14th May 1839 on the island of Tobago in the Caribbean at Merchiston, a small place approximately 24 km (15 mi) from Tobago's capital Scarborough, eight and a half months after the premature death of his father Charles Edward Groom (1815-1838), a very wealthy sugar plantation owner or manager, and his wife, Ann Napier (1815-1895). He would later (around 1865) add Napier (his mother’s maiden name) to his name, becoming Charles Ottley Groom Napier. Moving to England with his highly protective mother Ann Napier, he lived in Exeter, Devon as a young boy. After Charles caught whooping cough aged 9 they moved to Exmouth a few miles to the south in order to be by the seaside. As he continued for several years to suffer from delicate health his mother subsequently let their house in Exmouth and both she and Charles moved into lodgings when he was 11 years old. At first they resided at Budleigh Salterton, a town five miles east along the coast, but they then moved a little further inland to Honiton which had been recommended for its healthiness. However, due to the damp and rain, they later moved to a less wooded district of Devon and lived first at Devonshire Buildings in Weymouth and then to more commodious lodgings near the sea in a more central part of Weymouth town. Charles was a sickly child by all accounts, with precocious interests in natural history, the sciences, and antiquarianism. Around the age of 15, he and his mother moved to Lewes in East Sussex. In fact, Charles continued to live with his mother until his death. He is recorded in 1865 as living in the port of Bristol. In 1872 he was shown to be residing at 20 Maryland Road in London and in 1878 he resided at 18 Elgin Road, Harrow Road, London.

“My intellectual activity and vivid imagination was doubtless the cause of my delicacy. My mind was full of gigantic schemes, which were little influenced by my capacity for their execution.”

- Charles Ottley Groom Napier

- Charles Ottley Groom Napier

Stemming from his early interests in natural history he subsequently obtained a degree in geology and later became a member of the Geological Society of London. He was nominated to the Linnean Society of London and also joined as a Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society. He was elected a Fellow of the Geological Society of London on 24th May 1865, although he resigned in 1878, possibly over the publication of his “Burlington House” magazine (the cover of this implied that it had been produced under the auspices of the Geological Society of London, which it had not)!

Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and largest in Europe with more than 12.000 Fellows. It was formed on 13th October 1807 and received its Royal Charter on 23rd April 1825. Fellows are entitled to the post nominal FGS (Fellow of the Geological Society). The mission of the society is: “Making geologists acquainted with each other, stimulating their zeal, inducing them to adopt one nomenclature, facilitating the communication of new facts and ascertaining what is known in their science and what remains to be discovered”. Their motto is: Quicquid sub terra est (Whatever is Under the Earth).

Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It was formed in 1788 and received its Royal Charter on 26th March 1802. Fellowship requires nomination by at least one fellow, and election by a minimum of two thirds of those electors voting. Fellows may employ the post nominal letters FLS (Fellow of the Linnean Society). The Linnean Society possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature collections and publishes academic journals and books on plant and animal biology. In 1854 Charles Darwin was elected a fellow; he is undoubtedly the most illustrious scientist ever to appear on the membership rolls of the society. A product of the 18th Century enlightenment, the Society is the oldest extant biological society in the world, and is historically important as the venue for the first public presentation of the theory of evolution on 1st July 1858. Their motto is: Naturae Discere Mores (To Learn the Ways of Nature).

Royal Statistical Society is one of the established statistical societies. It has three main goals. The RSS is a British learned society for statistics, a professional body for statisticians, and a charity which promotes statistics for the public good. The society was founded in 1834 as the Statistical Society of London which became the Royal Statistical Society by Royal Charter in 1887, and merged with the Institute of Statisticians in 1993. The merger enabled the society to take on the role of a professional body as well as that of a learned society. Fellowship of the Royal Statistical Society is open to anyone with an interest in statistics. It is not restricted to only those with high achievement within the discipline. This distinguishes it from other learned societies, where usually the fellow grade is the highest grade in that discipline. As of 2019 the society claims more than 10,000 members around the world. The original seal had the motto: Aliis Exterendum (For Others to Thresh Out, i.e. interpret), but this separation was found to be a hindrance and the motto was dropped in later logos.

In January 1870, Charles Ottley Groom Napier (from now on I shall just refer to him as Napier) wrote to Charles Darwin and the transcript of that letter is:

20 Maryland Road | Paddington | W.

Janry 1870

To Charles Darwin Esqre, FRS

My dear Sir,

By desire of the late Lord Brougham I send you a copy of my new work The Book of Nature and the Book of Man, will you accept it in remembrance of his Lordship who had a very high opinion of the author of “Natural Selection” to which he was latterly a convert.

I regret much the delay in forwarding the book which is only just published. I should have liked to have sent it in the lifetime of Lord Brougham. Let it now be an olive leaf snatched from his tomb.

I remain yours most respectfully | C O Groom Napier

Janry 1870

To Charles Darwin Esqre, FRS

My dear Sir,

By desire of the late Lord Brougham I send you a copy of my new work The Book of Nature and the Book of Man, will you accept it in remembrance of his Lordship who had a very high opinion of the author of “Natural Selection” to which he was latterly a convert.

I regret much the delay in forwarding the book which is only just published. I should have liked to have sent it in the lifetime of Lord Brougham. Let it now be an olive leaf snatched from his tomb.

I remain yours most respectfully | C O Groom Napier

Henry Peter Brougham died in 1868 and it is most doubtful whether Napier personally knew Brougham or even whether Brougham wrote the preface to “The Book of Nature and the Book of Man” by Napier. Also, there are no copies of “The Book of Nature and the Book of Man” to be found in the Darwin Libraries at either Cambridge University or Down House, Kent.

In his 2004 book, “The Heretic in Darwin’s Court: The Life of Alfred Russel Wallace”, author Ross A. Slotten writes about English physicist and parapsychologist William Fletcher Barrett who had became interested in the paranormal in the 1860s after having an experience with mesmerism. Barrett believed that he had been witness to thought transference and by the 1870s he was investigating poltergeists. In September 1876, Barrett published a learned paper called “On Some Phenomena Associated with Abnormal Conditions of the Mind” outlining the result of these investigations. In the same year he was presenting his findings for the Anthropological Department of the British Association for Advancement of Science to around 1,200 people:

“Charles Ottley Groom-Napier, author of “The Book of Nature and the Book of Man”, next gave a long-winded account of his own spiritualist powers, including examples of his clairvoyant talents, which provoked grumbles from the audience. Some grew impatient with him and laughed at his descriptions of his experiences. “Give us facts!” someone shouted. Undeterred, Groom-Napier continued to give personal testimony until he was interrupted by more laughter, shouting, and ridicule and then finally told to shut up. Humiliated, he returned to his seat.”

Eccentric ancestry claims

From the late 1860s, bizarrely and for seemingly unknown reasons, Napier began to assume a series of self-aggrandising and ever grander titles (all entirely imaginary). A 200 plus page document was produced setting out the pedigree of himself and his mother, who assumed (or was given by her son) the title of Duchess of Mantua, Montferrat and Ferrara. A copy is in the British Library, and an online version is available from the National Library of Scotland - a link is in the references section at the bottom of this article. Napier started to style himself as the Prince (Duke) of Mantua and Montferrat with subsidiary titles as the Prince of Ferrera, Nevers, Rethel, and Alençon; Baron de Tobago; and Master of Lennox, Kilmahew, and Merchiston. By the time of his death he had adopted yet another name, Charles Bourbon d’Este Paleologus Gonzaga.

The House of Gonzaga is actually an Italian princely family that ruled Mantua in Lombardy, northern Italy from 1328 to 1708 (first as a captaincy-general, then margraviate, and finally duchy. They also ruled Monferrato in Piedmont and Nevers in France, as well as many other lesser fiefs throughout Europe. The family includes a saint, twelve cardinals, and also fourteen bishops. Two proper Gonzaga descendants became empresses of the Holy Roman Empire (Eleanora Gonzaga) and Eleonora Gonzaga-Nevers), and one became queen of Poland (Marie Louise Gonzaga).

The locations for all his assumed titles are as follows:

Mantua is a city and municipality in Lombardy, Italy and capital of the province of the same name.

Montferrat is part of the region of Piedmont in northern Italy.

Ferrera is a municipality in the Viamala Region in the Grisons, Switzerland. Nevers is the prefecture of the Nièvre Department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté Region in central France.

Rethel is a commune in the Ardennes Department in northern France.

Alençon is a commune in Normandy, France, capital of the Orne Department.

Tobago is an island within the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, located 22 miles northeast of the mainland of Trinidad and southeast of Grenada, about 99 miles off the coast of northeast Venezuela.

The Lennox is a region of Scotland centred on The Vale of Leven, including its great loch: Loch Lomond.

Kilmahew Castle is a ruined castle located just north of Cardross, in the area of Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

Merchiston is a residential estate in the southwest of Edinburgh, Scotland.

Napier clearly had a plan in his mind and was without doubt trying to advance his prestige, and naively attempting to spread his comparatively diminutive influence far and wide. He grew obsessed with his genealogy and insisted that he was descended from various European royal families and that he could trace his lineage all the way back to the Biblical King David. He worked with the genealogist John O’Hart and claimed that he could trace his ancestry to various European royal bloodlines or nobles through his mother Ann Napier. Works from John Riddell (a 19th century peerage lawyer) were published in 1879 attempting to link her to the Duchess of Mantua and Montferrat in Italy and the Scottish Clan Napier. These claims however were dismissed as a complete fabrication by most genealogists. Consequently, Napier’s academic reputation was heavily besmirched by scientists because his mineral collection was registered in the name of “Ex. Mus. P[rince] of Mantua & Monferrat”.

On 24th March 1879, Napier held a banquet for 7,000 guests in a specially-constructed pavilion at Greenwich in London, the walls of which were hung with 700 illuminated leaves of vellum illustrating his (purported) pedigree. Only vegetarian food was served, along with a drink of his devising that he called “curry champagne” made from a mixture of curry powder and ginger beer. There is no record of who, or how many, turned up, but apparently Napier himself was too ill to attend the festivities!

Napier never retracted his claims of ancestry and when he died of long-standing cardiac disease on 17th January 1894 his death was registered in London as that of “Charles de Bourbon d'Este Paleologues Gonzaga, prince of Mantua and Montferrat”. When his mother died a year later, having assumed the title of Dowager Duchess of Mantua, she was registered under the name Ann de B.D.P. Gonzaga. In October 1895, the Horniman Museum in Forest Hill, south London, bought a significant amount of Papua New Guinea material from the Mantua collection at an auction.

In one of his later volumes of work entitled; “Works of H.R. and M.S.H. the Prince of Mantua and Montferrat, Prince of Ferrara, Nevers, Réthel, and Alençon. London” (Dulau and Co, 1886), Napier had prefaced the book with sixty-four pages of fictitious rave reviews and testimonials provided by such illustrious individuals as Victor Hugo (“miraculous”), Michael Faraday (“a marvel”), Anthony Trollope (“too much for this wicked world”), Elizabeth Barret Browning, Charles Darwin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Abraham Lincoln, and Pope Pius IX. All of these reviews were fraudulent, all of them invented by Napier. However, conveniently for him, none of these people were available to dispute the attributions since they were all recently deceased!

Prize medals

He also decided he was going to reintroduce a “Mantua & Montferrat Medal Fund”, which he claimed had been created by his ancestor Lodovico Gonzaga in the 14th century to confer recognition on men eminent in arts, letters and science! Harking back to the genuine medals created in Renaissance Italy by the nobility of Mantua and other city states, Napier initiated production of a gilded bronze “Prince of Mantua and Montferrat’s Prize Medal” to support his assumed lineage. A total of twenty-four medals were issued by him in 1879 and he bestowed them (by post!) on various eminent men - a link to the full list is in the references section below.

The medals were sent to the recipients, who were instructed, via an accompanying letter, to acknowledge receipt upon delivery and write back to Napier with a photograph of themselves with the medal. He collated and recorded the replies, and claimed that all the recipients had replied as instructed by 1883. The medals were all identical except for the name of the recipient; some including British statesman, politician and Prime Minister (although not at the time the medal was issued) William Gladstone refused the “honour”; British botanist and explorer Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin’s closest friend) received his medal for “geographical botany”. His reply to the “Prince” was sent from the Royal Botanical Gardens Kew, where Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker was Director, on the 4th October 1882. Hooker was said to have accepted the medal with “guarded courtesy”. Mention of it is noticeably absent from the extensive list of medals, honours and awards that were received by Hooker between 1839 and 1908; A medal was also sent to British biologist, comparative anatomist and palaeontologist Sir Richard Owen (generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils). This medal is now held in the Natural History Museum, London; Another medal was sent to the British writer, philosopher, art critic, and polymath John Ruskin (who wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany, and political economy). Ruskin replied enthusiastically to Napier from his home in Herne Hill London on 2nd April 1882, but did not include a photograph. His medal is in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Regarding the details that were shown on the medals, the obverse features a profile portrait of an as-yet unidentified man and the reverse lists claimed past recipients; Raphael, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Dante, Tasso, Columbus, Ariosto, Galileo, Copernicus, Racine, Molière, Cervantes, Milton, Shakespeare, Newton, Napoleon, and Cuvier. Napier was also included between Shakespeare and Newton!

At the 1879 banquet mentioned earlier, it is understood that the great and the good were going to be presented with medals there as well (the reverse had a space for naming), but for some unknown reason this never came about and unnamed medal examples remain extremely rare.

British Israelism

Napier read a paper to the London Anthropological Society in 1875, entitled "Where are the Lost Tribes of Israel". He believed that the British descended from the Ten Lost Tribes and was a personal friend of Edward Hine who was an influential proponent of British Israelism in the 1870s and 1880s. Hine went as far as to conclude that "It is an utter impossibility for England ever to be defeated. And this is another result arising entirely from the fact of our being Israel." Hine departed England for the United States in 1884, where he promoted the idea that Americans were the lost tribe of Manasseh, whereas England was the lost tribe of Ephraim.

British Israelism (also called Anglo-Israelism) is the belief that people of Western European descent, particularly those in Great Britain, are the direct lineal descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. The concept often includes the belief that the British Royal Family is directly descended from the line of King David.

British Israelism as an established movement traces itself back to the 17th century. Adriaan van der Schrieck (1560–1621) a Flemish language researcher in 1614 wrote, “...the Netherlanders with the Gauls and Germans together in the earliest times were called: Celts, who are come out of the Hebrews”.

In a 2014 book called “The Evolutionist: The Strange tale of Alfred Russel Wallace”, author Avi Sirlin writes about a presentation at the British Association for Advancement of Science in Glasgow on 12th September 1876, where Napier is mentioned.

“From the first row Sir William Crookes signalled for the floor. In that dolorous tone known to all, the discover of thallium and inventor of the radiometer reminded the audience he had produced his own thorough report on spiritual phenomena two years earlier. This elicited groans from the uncouth quarter. Undaunted, Crookes iterated that his own vigorous experiments validated the existence of spiritual phenomena. Thus he respectfully disagreed with Professor William Barrett’s excessive note of caution. The Association could do well to forge ahead and establish spiritualism as the newest branch of natural science. Charles Ottley Groom-Napier sprang to his feet. Little choice for Alfred Russel Wallace (President of the Association’s Biology Section), but to recognise the prominent geologist, Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society and member of the Linnean Society - also the self-proclaimed Prince of Mantua and Montferrat and avowed descendant of King David. Groom-Napier launched into a long-winded and unintelligible history of his own investigation. Genuine unrest now gained foothold. Concluding, Groom-Napier appealed to Wallace directly, ‘Mr President, might I add that we British, as descendants of the ten lost tribes of Israel, have a duty - ‘. The gentleman never got to finish for all the outcries. The audience’s displeasure only deepened when, out of fairness, Wallace granted the floor to Reverend Thompson. The Reverend predictably denounced spiritualist phenomena ...”

Literature

Napier wrote prolifically on the natural sciences too and, for much of his career, he was a conventional and well respected author. He published numerous learned articles and his books included:

“The Food, Use, and Beauty of British Birds: An Essay : Accompanied by a Catalogue, of All the British Birds.” (1865)

“Miscellanea Anthropologica, or Illustrations of Races: Three Essays Reprinted From the Anth[Ropological] Jour[Nal], Etc.” (1867)

“Variations in the Colour, Form and Size of the Eggs of Birds” (1868)

“The Book of Nature and the Book of Man: In Which Is Accepted As the Type of Creation, the Microcosm, the Great Pivot On Which All Lower Forms of Life Turn.” (1870)

“Vegetarianism in the Bible” (1879)

“Lakes and Rivers [Natural History Rambles]” (1879); this is probably the most commonly encountered Napier work these days.

“Works of H.R. and M.S.H. the Prince of Mantua and Montferrat, Prince of Ferrara, Nevers, Réthel, and Alençon” (1886)

Napier even wrote an autobiographical book, called “Tommy Try And What He Did In Science” (1869), engraved with forty-six illustrations. I consider myself fortunate to own a 1st edition of this extremely rare book, in addition to owning a 2nd edition (1880) of Lakes and Rivers [Natural History Rambles], both in great condition.

Works of H.R. and M.S.H. the Prince of Mantua and Montferrat, Prince of Ferrara, Nevers, Réthel, and Alençon (1886)

Additionally, Napier contributed significantly to a book by French scientist and writer Louis Figuier called “The Ocean World: Being a Description of the Sea and its Living Inhabitants” (1868). Napier rearranged the whole of the Mollusca section with the chapters on conchology being revised and enlarged by him for the 1869 edition. A link to a free copy of the full book (Project Gutenberg eBook) is in the references section below.

Various collections

As a prominent collector, Napier was voracious and he acquired a large number of mineral, fossil, and plant specimens from around the world. Many of these were later sold to the Natural History Museum, London. He also amassed a big collection of miscellaneous prints.

Eventually the mineral portion of his collection was purchased by the German mineral dealer Friedrich Krantz, taken to Bonn, and dispersed.

Napier bought the personal collection of fossils from James Tennant, who was a British mineralogist and mineralogist to Queen Victoria. The Tennant collection was later purchased by Robert Damon and sold to the Western Australian Museum in Perth where it remains today.

A large part of his herbarium is currently preserved in the United Kingdom at Bolton Museum, Greater Manchester, England. A link in the references section below provides a list of the herbaria specimens collected by Napier.

In 1878, Napier sold 651 prints to the British Museum. These can be viewed through their online collection - a link is in the references section below.

Mineral specimens

Mindat members might be familiar with or maybe even have in their possession, labelled or otherwise, old mineral specimens of Charles Ottley Groom Napier. Notwithstanding his eccentricities and somewhat poorly considered reputation I consider myself lucky to own several of his labelled specimens; a calcite twinned scalenohedron crystal specimen from Somerset in England, a rhombohedral calcite cleavage specimen from Cornwall in England, and a specimen of plagioclase (oligoclase) crystals perched on a granitoid matrix from Switzerland (shown below). Napier specimens do occasionally appear on the market and the original labels on them are quite distinctive with their thin red lines/borders and cursive writing. The labels often include “Mus. M. & M.” printed in red upon them, or the much rarer “Ex. Mus. P. Mantua & Montferrat.” (also printed in red). Seemingly, more often than not locations given for specimens are not very accurate or can be rather vague to say the least. Napier was also in the habit and well known for making up localities to "increase" the rarity and value of his specimens!

Other examples of minerals with labels:

Examples of labels only:

Conclusion

His youthful enthusiasm for more traditional sciences, such as biology and chemistry, was somewhat dampened in later years and nowhere is this better illustrated than in the small extract from his 1869 book “Tommy Try And What He Did In Science”, as shown below.

“I could hardly describe my feelings on first meeting men of science, of whom I had formed wonderful ideas. I imagined them to be free from the defects to which ordinary men are subject - Adams, enumerating lower forms of life over which they watched with the tenderness, dignity, and understanding of master-minds. When in after years I had a more extensive acquaintance with scientific men, I found that they in nowise differed from the unlearned. They were subject to the same meanness, the same narrowness of mind, love of the minute, and contempt for the great; the same bitter struggle for an existence; the same tendency to gather under the mantle of knowledge an epitome of every vice common to man, which could find no lodgment on the statue of truth unless "ventilation" were impeded, as it often is, by cliques and learned corporations. WHATEVER SCIENCE WAS IN FORMER AGES, IS NOW ONLY EXPOUNDED BY OUR SOCIETY.”

- Charles Ottley Groom Napier

- Charles Ottley Groom Napier

However, he did retain huge respect and a great deal of enthusiasm about the life and works in particular of the German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science, Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt, who died in 1859. Napier also took intense delight in the literary works of William Shakespeare and in later years he developed an avid interest in the pseudoscience of phrenology which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.

Napier lived at a time called the Age of Enlightenment (also known as the Age of Reason or simply Enlightenment), when the intellectual and philosophical movement dominated the world of ideas in Europe. Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies, which had largely replaced universities as centres of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were also the backbone of the maturation of the scientific profession. Another important development was the popularisation of science among an increasingly literate population. A genre that greatly rose in importance was that of scientific literature. Natural history in particular became increasingly popular among the upper classes. Knowledge was based on experimentation, which had to be witnessed to provide proper empirical legitimacy. However, not just any witness was considered to be credible: “Oxford professors were accounted more reliable witnesses than Oxfordshire peasants’”. Two factors were taken into account: a witness's knowledge in the area and a witness's “moral constitution”. In other words, only the civil society and people of high standing were legitimately considered worthy. Social status, ladder climbing and one-upmanship all played an important role in determining a person’s place within society. It was also probably fairly easy to find yourself “backing the wrong theory” during a period when so much was new and often fast changing as well!

I suspect that Charles Ottley Groom Napier was ultimately just doing what he thought was best in his own mind and he was attempting to advance himself by whatever means he could in order to find a worthy place in the increasingly competitive, sometimes pretty ruthless and unsparing, dog-eat-dog environment that he found himself in. My personal view is that he was a clever man, albeit with obvious flaws in his character, and sometimes he found himself out of his depth. He also made a few wrong choices along the way of life perhaps, as is often the case! He seems to have done no harm and there is evidence that he did make a contribution (however large or small is open to much debate) in the worlds of both literature and science. Ultimately, it seems he secured a place in the annals of history and will be remembered for the small part he played in the 19th century.

References

The content of this article was researched from a number of different sources and much of the information has been duplicated many times elsewhere. As a result, the “fons et origo” is unknown in many cases, or else is otherwise too ambiguous to accurately credit. Notwithstanding unattributable citations, documented references have been acknowledged within the article itself where they are known.The story of Charles Ottley Groom Napier’s life has been covered by others, including Brian William Fox FLS (1929-1999) in the 1993 edition of The Linnean, no. 9 (2), pp. 26-28. Many sources cast doubt on the man, his works and abilities.

https://ca1-tls.edcdn.com/Linnean-9-2-1993.pdf

The Pedigree of Her Royal and Most Serene Highness THE DUCHESS OF MANTUA, MONTFERRAT, AND FERRARA; Nevers, Rethel, and Alengon; Countess of Lennox, Fife, and Menteth; Baroness of Tabago;

In which is traced her Descent from King David, the Houses of Gonzaga, Paleologus, Este, Bourbon, Lennox, Napier, etc.

https://digital.nls.uk/histories-of-scottish-families/archive/95659015#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=8&xywh=-150%2C-1%2C2798%2C3201

Full list of Prince of Mantua medal recipients as given in the

‘Pedigree of Her Royal and most serene Highness the Duchess of

Mantua, Montferrat, and Ferrara’ (1885).

https://ca1-tls.edcdn.com/MantuaMedalRecipients.pdf

Project Gutenberg eBook (free copy) “The Ocean World: Being a Description of the Sea and its Living Inhabitants” (1869), by Louis Figuier with revisions by Charles Ottley Groom Napier.

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/47626/pg47626-images.html

Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland (label examples and search for specimens collected Charles Ottley Groom Napier.

https://herbariaunited.org/collector/11109/

British Museum - Charles Ottley Groom Napier print collection. Click on related objects after following the link.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG246194

Article has been viewed at least 5025 times.