Home PageAbout MindatThe Mindat ManualHistory of MindatCopyright StatusWho We AreContact UsAdvertise on Mindat

Donate to MindatCorporate SponsorshipSponsor a PageSponsored PagesMindat AdvertisersAdvertise on Mindat

Learning CenterWhat is a mineral?The most common minerals on earthInformation for EducatorsMindat ArticlesThe ElementsThe Rock H. Currier Digital LibraryGeologic Time

Minerals by PropertiesMinerals by ChemistryAdvanced Locality SearchRandom MineralRandom LocalitySearch by minIDLocalities Near MeSearch ArticlesSearch GlossaryMore Search Options

The Mindat ManualAdd a New PhotoRate PhotosLocality Edit ReportCoordinate Completion ReportAdd Glossary Item

Mining CompaniesStatisticsUsersMineral MuseumsClubs & OrganizationsMineral Shows & EventsThe Mindat DirectoryDevice SettingsThe Mineral Quiz

Photo SearchPhoto GalleriesSearch by ColorNew Photos TodayNew Photos YesterdayMembers' Photo GalleriesPast Photo of the Day GalleryPhotography

╳Discussions

💬 Home🔎 Search📅 LatestGroups

EducationOpen discussion area.Fakes & FraudsOpen discussion area.Field CollectingOpen discussion area.FossilsOpen discussion area.Gems and GemologyOpen discussion area.GeneralOpen discussion area.How to ContributeOpen discussion area.Identity HelpOpen discussion area.Improving Mindat.orgOpen discussion area.LocalitiesOpen discussion area.Lost and Stolen SpecimensOpen discussion area.MarketplaceOpen discussion area.MeteoritesOpen discussion area.Mindat ProductsOpen discussion area.Mineral ExchangesOpen discussion area.Mineral PhotographyOpen discussion area.Mineral ShowsOpen discussion area.Mineralogical ClassificationOpen discussion area.Mineralogy CourseOpen discussion area.MineralsOpen discussion area.Minerals and MuseumsOpen discussion area.PhotosOpen discussion area.Techniques for CollectorsOpen discussion area.The Rock H. Currier Digital LibraryOpen discussion area.UV MineralsOpen discussion area.Recent Images in Discussions

GeneralOrigin of the name peridot

30th Jun 2014 09:11 UTCOlav Revheim Manager

Peridot is most commonly believed to have originated from persian and or arabic faridat (faridet), meaning gem, whereas The Oxford English Dictionary suggests an alteration of Anglo–Norman pedoretés (classical Latin pæderot-), believed to possibly be a kind of opal.

Augusto Castellani(1870) in his "Delle gemme: notizie raccolte" offers an alternative explanation: "Trovandosi generalmente inchiuso nei basalti e nelle sabbie vulchaniche, esso ebbe il nome che porta del greco Περί , interno, e δέω possibly legare, cioe legato interno"

i.e a constructed term - tied to the edge - in allusion to the occurrence of peridot as green bombs in lavas.

I am aware that the name peridot has been occasionally used from the mid 13th century, but is was not commonly used until the 18th and 19th century, then predominantly by the French. Is Castellani's explanation a theoretically viable alternative ?

Thanks

Olav

30th Jun 2014 10:54 UTCVolker Betz 🌟 Expert

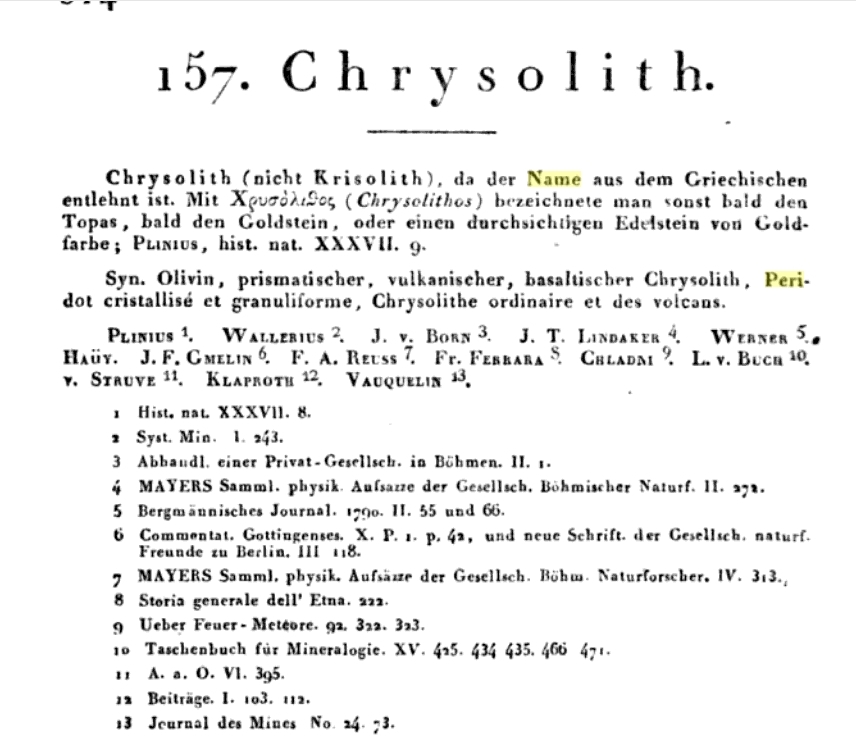

I have some interest in Peridote and did some resarch in the past. Most authors say that it was used by Hauy for olivine and this is cited frequently.

In German literature of the early 19th century the name is frequently used for olivine.

The gemmy version was still often named chrysolite, a name which was also used for cut apatite and other stones with similar colour.

I belive that your italian source was a litte influenced by patriotism.

Attached an excerpt from Handbuch der Oryktognosie von Carl Caesar von Leonhard, Heidelberg 1822

I think the name peridot is really of still unknown, there are no reliable sources.

Volker

30th Jun 2014 11:07 UTCOwen Melfyn Lewis

I think that all lexicographers can do is to look for early forms of the word used in contexts that seem to associate with a clear meaning. Castellani may or may not be right but he needed to make his case rather than simply state an unsuppported conclusion. Without clear evidence that Castellani's conclusion is simply supposition and one should prefer the much older Norman-French (rather than Norman-English) at the root.

What, if anything is there in Pliny's writings to give weight to Castellani's opinion?

30th Jun 2014 17:54 UTCOlav Revheim Manager

I have done a bit more research and it does seem that Pliny may be one of the sources of the name peridot: He use the name paederos, but for a white stone, believed to be a sort of opal (or possibly chalcedony), see link. This stone is mentioned by Isodore of Seville (~600 AD) as "paederota" but without any further details on appearance. Ware (1705) quotes an English text from 1245 that use peridot in the spelling we use today, but without saying anything about the stone itself. The Middle English Dictionary link lists peridot in several different spellings, and also lists several examples on it's use in both english and latin. One of them describes peridot as a silver-like stone and Agricola (1576) , which is one of the finest mineralogist from this period lists paederotae and paederos as a variety of opal.

At some stage the name peridot also became the name of a green stone. One source from 1422 mentions peridot as a common (vulgarites) name for a green gem, as does several others. Remondini di Venezia, (1781) classifies peridot as a imperfect and soft form of emerald. Stephen Weston(1805) is the earliest I have found that indicates that the name "peridot" may originate from teh arabic "faridat" i.e gem.

It was not until Hauy and other French mineralogists started to use the name peridot on green "bombs" in lavas of isle of Bourbon the name came in common use. I have not been able to find any of Hauy's original texts to see if he gives any clue on where he got the name peridot from. That Hauy could define a new name based on the greek Περί and δέω does not seem unreasonable to me, but I have no idea whether this is plausible or not.

I would appreciate if anyone could provide any information on Hauy's use of the name Peridot.

Thanks

:-)

Olav

30th Jun 2014 22:50 UTCOwen Melfyn Lewis

The stone we know as peridot was mined on St John's Island in the Red Sea by the Egyptians. In those times Egypt was largely under the control of Rome.. If that was the first source of peridot, it would not have been associated (at that time) with any volcano - and there would, almost certainly, have been a Latin word for it. Peridot existed as a gem in the time of Pliny but whether or not he included it in his listing of gens, I don't know - but it would seem likely.

Without precising the history of the British Isles, It was, in the case of mainland Britain, one of repeated invasion and part-conquest until 1066 when the Normans (themslves Viking raiders of the north-west French coast who had in time settled there), conquered the lands previously ruled by the Anglo-Saxons and Norwegian Vikings (invaders both) who, between them, rules by conquest much the same area es is now England. For over 300 years after 1066, what was early English was eclipsed. The country was administered in Norman-French; its laws were written in Norman-French and that was the language of legal proceedings. The language of the Church - the keeper of all academic knowledge was Latin throughout Europe and remained so well into the 16th C. Only from the late 1300's did English become accepted once again as the common language of all English people and from the early 1400's was used in Court and for legal purposes.

Accordingly and IMHO , it is surely to Latin (and from there to Norman-French?) that we must look for the roots of Peridot. But, as already indicated , this is no support for Castellani's veiw that the origin of the word and its meaning are to be found in Greek.

30th Jun 2014 23:09 UTCJosé Zendrera 🌟 Manager

http://www.google.es/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=9&ved=0CEAQFjAI&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.gia.edu%2Fcs%2FSatellite%3Fblobcol%3Dgfile%26blobheader%3Dapplication%252Fpdf%26blobheadername1%3DContent-Disposition%26blobheadername2%3DMDT-Type%26blobheadername3%3DContent-Type%26blobheadervalue1%3Dattachment%253B%2Bfilename%253DZabargad%253A-The-Ancient-Peridot-Island-in-The-Red-Sea%26blobheadervalue2%3Dabinary%253B%2Bcharset%253DUTF-8%26blobheadervalue3%3Dapplication%252Funknown%26blobkey%3Did%26blobtable%3DGIA_DocumentFile%26blobwhere%3D1355958503462%26ssbinary%3Dtrue&ei=t9qxU6apLOq20QX_xIHQAg&usg=AFQjCNHSdL90rA9GoMwyYTL3OUhLQja8MA&sig2=4o5hcZIvnsevBoCMEp1guQ&bvm=bv.69837884,d.bGE&cad=rja

1st Jul 2014 09:18 UTCOlav Revheim Manager

A very interesting read. :-)

Olav

1st Jul 2014 09:53 UTCLuca Baralis Expert

-------------------------------------------------------

> Accordingly and IMHO , it is surely to Latin (and

> from there to Norman-French?) that we must look

> for the roots of Peridot. But, as already

> indicated , this is no support for Castellani's

> veiw that the origin of the word and its meaning

> are to be found in Greek.

IMHO, if Egyptian dug it, they should had an egyptian name for it, but, sure, there were also a latin one and probably a greek one, too.

1st Jul 2014 09:54 UTCLefteris Rantos Expert

I have no clear opinion on the origin of the name "Peridot", but a Greek root (from the words περί = around and δέω = tie; bind) could make sense.

Lefteris.

1st Jul 2014 10:33 UTCOwen Melfyn Lewis

Topazos was one of the stones said to have been set in breastplate of the high priest of the Israelites. War this topaz, peridot or something else entirely? It seems we shall never know. What does seem certain though is that 'topazos' is not the root from which 'peridot' is derived.

Olav, re. your wish to read Hauy's works. Try the Bibliotheque national de France. It has a good digital online service and they will print reproductions to order as well.

1st Jul 2014 16:02 UTCOlav Revheim Manager

Thank you very much!!

I did some brief browsing in the archives of Bibliotheque national de France without getting any closer to the origin of the word peridot. It does however seem that it was Hauy that introduced the name into modern mineralogy and made sure it became commonly used in the mineralogical literature.

:)-D

Olav

1st Jul 2014 19:19 UTCVandall Thomas King Manager

1st Jul 2014 19:25 UTCDavid Von Bargen Manager

Also used for greenish-yellow tourmaline

Pierre de Rosnel (1668)

http://books.google.com/books?id=hs3_Uh3KnJEC&pg=PA59&dq=pierre+de+rosnel+peridot&hl=en&sa=X&ei=NwKzU-iTJsW58gGMxIGYCA&ved=0CD8Q6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=pierre%20de%20rosnel%20peridot&f=false

One thing that sort of argues against an Arabic origin for the name is that they did have a specific name already (13th century) for peridot - zabardjad.

1st Jul 2014 21:12 UTCVandall Thomas King Manager

1st Jul 2014 21:40 UTCDavid Von Bargen Manager

1st Jul 2014 22:18 UTCVandall Thomas King Manager

2nd Jul 2014 07:24 UTCOlav Revheim Manager

The De Rosnel reference is great. It places the name peridot in French gem literature before the science of mineralogy emerged. It is not possible from De Rosnel to say which mineral(s?) he is refering to, as his peridot is a green(ish) rare stone of low value, unless it is extraordinary large. The only physical characteristics he gives is that peridot is harder then emerald, which tells me that his emerald is probably not the same mineral that we call emerald today.

Olav

2nd Jul 2014 20:05 UTCRonald J. Pellar Expert

Could it have been a green sapphire?

3rd Jul 2014 11:42 UTCOlav Revheim Manager

Thank you for your interest in this thread. Low grade green sapphire may be an alternative, but since the emerald could be almost any green green gem it is really hard to tell.

Thanks

Olav

3rd Jul 2014 15:22 UTCVandall Thomas King Manager

3rd Jul 2014 16:56 UTCOwen Melfyn Lewis

In general I'm with you Van; it's fun but not a serious exercise to tie root names to gems from before the proper classification of minerals.

Besides, as all *gemmologists* know, 'peridot' is not a synonym for olivine. Rather, it is the name for a quite tightly defined percentage mix in the forsterite-fayalite solid solution series. This percentage can be verified by chemical analysis but is also adequately differentiated by by its RIs, birefringence and SG.

Mineralogists cannot have their cake and eat it. If they choose not include species' varieties in their classification system, they need to accept that others who need a sound and verifiable means for differentiating one variety of a species or position in a solid solution series from another will set the lexicon and standards for commercially important varieties.

4th Jul 2014 09:51 UTCOlav Revheim Manager

Thank you for sharing your thoughts and insight on this matter. I agree with you that it is fascinating to go back in history to try to find the root source of information. I started this thread as I am in the processes of writing an article on the St. John/ Zabargad peridots and found more questions than answers in my research in older literature, and definitive answers can not easily be found. This was of course as I expected, but it is nevertheless educational to read old literature.

Today, such research is easier than ever before. Vast volumes of information is available on the internet and it is a matter of minutes to find it. Theophrastus' work "De Lapidibus" or "On stones" is available for anyone to read, see here and here. His smaragdus seems to be a partly water soluble copper mineral rather than peridot or emerald.

The two ancient works that have impressed me the most are Pliny the Elders Natural History (79 A.D) see here and Al Biruni's ( ~1000 AD) book on precious stones, see here.

By the way,Owen, who in the gemological world is it that has the authority to define names such as peridot, and are there an official list of approved names and definitions?

Thanks

Olav

4th Jul 2014 13:39 UTCRalph S Bottrill 🌟 Manager

Interesting, but you rarely see gem varieties defined chemically, and I really doubt that most gemmologists would care as long as the colour was right. Probably the only likely restraint is Mg>Fe, but even then i doubt that a gemmy olivine with Fe>Mg would not be called peridot if the colour was close enough. It would be great to add chemical limits to many varieties if we can get anything authoritative, even though purists may not care much (on either side of the fence).

4th Jul 2014 14:45 UTCVandall Thomas King Manager

4th Jul 2014 15:38 UTCOwen Melfyn Lewis

-------------------------------------------------------

> By the way,Owen, who in the gemological world is

> it that has the authority to define names such as

> peridot, and are there an official list of

> approved names and definitions?

Ralph Bottrill wrote:

------------------------------------------------------

> Interesting, but you rarely see gem varieties defined

> chemically, and I really doubt that most

> gemmologists would care as long as the colour

> was right. Probably the only likely restraint is

> Mg>Fe, but even then i doubt that a gemmy olivine

>with Fe>Mg would not be called peridot if the colour

> was close enough. It would be great to add chemical

> limits to many varieties if we can get anything

> authoritative, even though purists may not care

>much (on either side of the fence).

>

The nearest thing to a naming authority is CIBJO, the international governing body for the jewellery trade, which published a lexicon of names for gems, gem treatments etc. In turn, CIBJO is informed by several gemmological text books and the academic journals of the various national gemmological associations. In short, the approach is collegial and consensual. That said, IMHO, it loses it's way more often than it should.

All much too big a topic to do justice to in a post here :-) But here are some touchstones. Gemmology is a specialism that largely grew out of mineralogy in the early part of the last century. Most but by no means all gems are minerals; accordingly gemmology, in modern times, is led in the naming of gems by using the names of the mineral species (where is is *useful* to do so - which is most of the time but not all of the time). There are many gemstones that were traded under certain names for hundreds - thousands - of years. Most of these names are retained in use though their application has been narrowed to material that can now be should be all of the same type. Classic examples of this are the names peridot, ruby, sapphire and emerald.

It is most probable that pre-1800-ish many different green minerals were traded under the name peridot. Certainly, there are 18th C records of what has since been discovered to be tourmaline being honestly traded out of Brazil as emerald. And the trading of red spinel as ruby is a famous example of one name being applied to different minerals with similar colouration. These practices continued as wide spread - both by honest mistake and by dishonest intent - into the 20th C. Gemmology was brought into being largely to sort this mess out and to keep the gem trade honest, fair and reputable.

So how and why does the close definition of peridot come about - and why is it at variance to the practice in mineralogy that would call it either forsterite or maybe green forsterite if colour was of adjectival use in a given context. To the gemmologist, it is important to differentiate (name differently) peridot from forsterite which has a much lower trade value and also to differentiate from fayalite which has little to no gem trade value. The green hue that is 'peridot' exists only when the Fe present in a forsterite-fayalite series specimen is 10-12%. Less Fe and the stone loses value by becoming too yellow (even colourless). More and unpleasant gray or brown overtones creep in.

The gemmlogist identifies peridot principally by the following characteristics:

1. Its RIs and birefringence

2. Its SG

3. A dichroic show of green and yellowish green colours.

In short, the gemmologist will avoid fussy chemical analysis by measuring to within fairly close tolerances the optical parameters above, cross referencing with the density of the material and dichroic show. The attractiveness of the colour and the relatively unflawed size will determine the trade value of a piece on a non-linear scale set by market demand.

If (as was once the case) one has to ID by colour alone, it is not hard to think some peridot is emerald. Do the above tests and there is no way the two can be confused. There is a well known example, in Koeln Cathedral for hundred of years, of 'emeralds' that are peridots.

5th Jul 2014 06:11 UTCOlav Revheim Manager

Thank you for your thorough and informative reply :-)

Olav

5th Jul 2014 14:24 UTCOwen Melfyn Lewis

-------------------------------------------------------

> Owen, I did not say that peridot was a synonym for

> olivene.

Sorry Van, that was an inference I drew from your words. My mistake.

> Today, peridot is an olivine mineral, not

> any other group.

Yes.

> Historically, smaragdus was used

> for several green grems. Smaragdus is not just

> emerald.

My point is that that there are at least 18 European languages that obviously draw their present name for the emerald variety of beryl from the obvious common root of 'smaragdus' I know of no other stone that draws its modern name from the root 'smaragdus'. That in the past stones were often bought and sold under an incorrect description is something on which we agree but in the modern gem lexicon, only the emerald variety of beryl can link its modern name to to the ancient smaragdus, All else was cut away in the last century and, renamed in the last century.

Or should have been.... lucky purchasers of a quantity of spinel crystals just occasionally find that one of them is a taaffeite, much to their gain and the loss of an over hasty dealer.

Mindat.org is an outreach project of the Hudson Institute of Mineralogy, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.

Copyright © mindat.org and the Hudson Institute of Mineralogy 1993-2024, except where stated. Most political location boundaries are © OpenStreetMap contributors. Mindat.org relies on the contributions of thousands of members and supporters. Founded in 2000 by Jolyon Ralph.

Privacy Policy - Terms & Conditions - Contact Us / DMCA issues - Report a bug/vulnerability Current server date and time: May 9, 2024 20:07:36

Copyright © mindat.org and the Hudson Institute of Mineralogy 1993-2024, except where stated. Most political location boundaries are © OpenStreetMap contributors. Mindat.org relies on the contributions of thousands of members and supporters. Founded in 2000 by Jolyon Ralph.

Privacy Policy - Terms & Conditions - Contact Us / DMCA issues - Report a bug/vulnerability Current server date and time: May 9, 2024 20:07:36